In a country of five million people, there are only 24 dentists and around 50 doctors—most of them concentrated in Monrovia. The healthcare system is still recovering from the devastating effects of Ebola, which wiped out about 49% of healthcare workers, and from the brutal civil war that exhausted the system.

It was here, in the heart of Liberia, that I had my first malaria infection—deep in the middle of one of the world’s largest (sometimes second-largest) rubber tree forests.

Having malaria makes you completely dependent on locals. No fancy travel insurance or phone apps will help you find the right place for quick treatment.

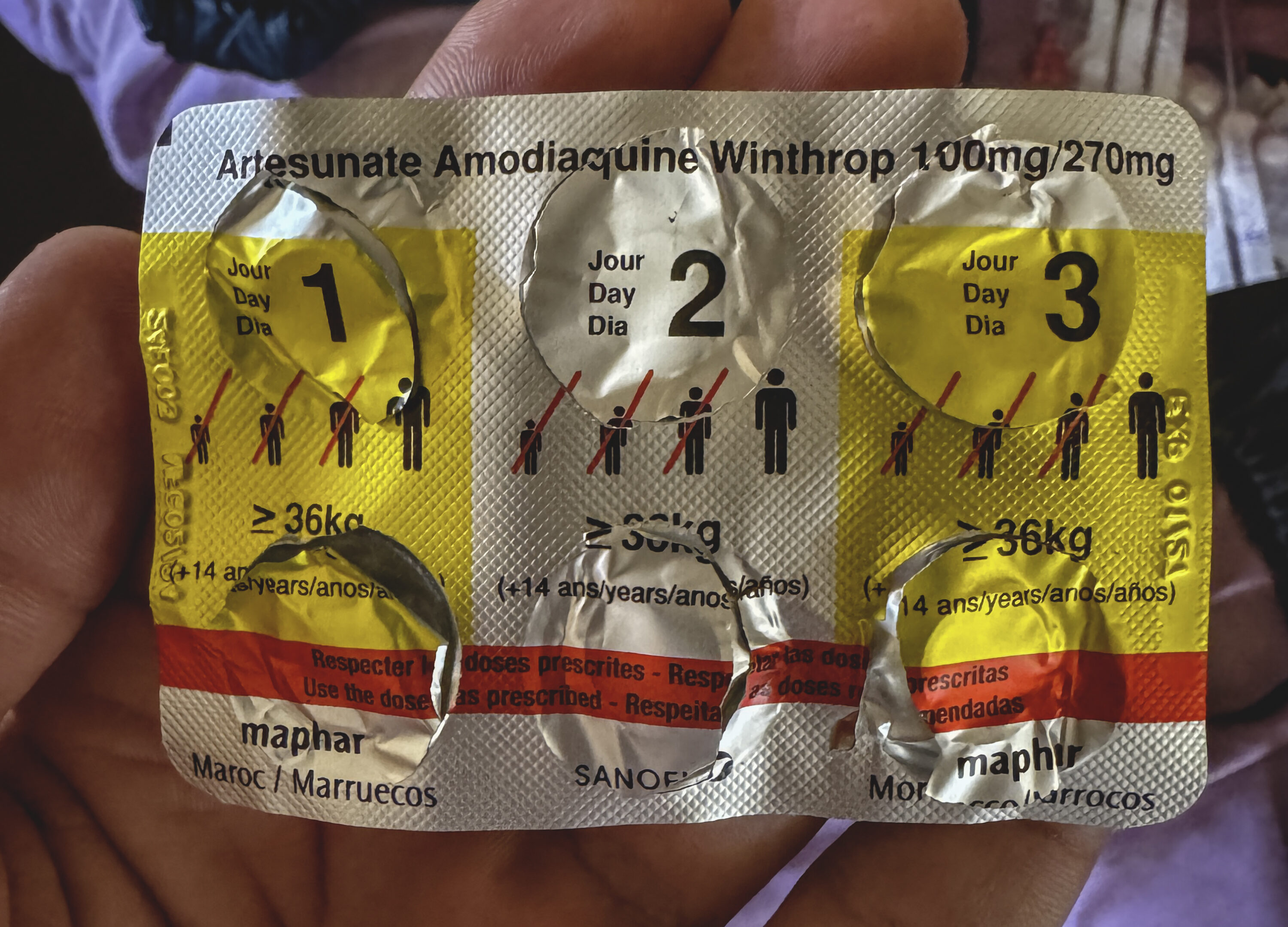

We carry Malarone, but we don’t take it. We try to live like the locals, who simply don’t have the means to afford it. However, in emergencies, we can take four pills a day for four days—just enough to hold on until we reach a health center that offers microscopic testing and the right treatment for the specific malaria strain I had.

Luckily, a passing motorcyclist pointed us to a small health centre about 1.5 km away. I have no idea how I found the strength to cycle there. Looking back, I probably had malaria since Monrovia—five days earlier.

we arrived there but they didn’t have the right test. but they gave many emergency injections.

Malaria needs to be treated quickly; otherwise, it can become fatal within days.

then arranged an “ambulance/an old car from the 70s barely functioning” that took me to the main hospital, about 50 km away, which was worse than cycling. It took us hours to get there.

At the hospital, they performed a microscopic test, confirmed the diagnosis, provided me with medication, and sent us back to the small health center where we had left our bikes. The staff there allowed us to stay for three days until I recovered.

the medication are strong and I had no energy, was disoriented, and couldn’t find nutritious food. Thankfully, the staff prepared meals for us every day, which helped me regain some strength.

On the third day, we left following the doctor’s advice. I managed to cycle 23 km before I had to stop near a school—I simply couldn’t go any further.

We had a 23 km stretch of unpaved road that felt like a roller coaster before arriving at Kakata, where there was a police checkpoint. So far, the Liberian police and imitation officers have proved to be the most annoying I have encountered in my travels across 30 countries.The first police officer took us to an office to check our passports. After five minutes of looking over our documents and speaking nonsense, we moved on to the second check with an immigration officer who appeared to be very drunk.

“What do you want?”

“I’m the immigration officer.”

“Okay,” I replied.

“I can check your bags if I want,

“Do you want me to open them for you?

If I want, I can. Do you see my badge and my weapon?”

“Alright, do you want to check the bags then?” I asked.

“Yes, open them.”

I opened the bags, and he glanced inside from above without really inspecting them. It was frustrating to see the rules being used as tools for blackmail. They usually extort 50 LD from locals, and they aren’t used to someone challenging their “power.”After we finished, he began again with more nonsense that I could hardly understand. After half an hour, I asked for the second time in Liberia,

“Is everything alright? Did we do anything wrong?”

He replied, “No.”

“Okay, if you don’t let us go, we will immediately call the German embassy.”

“Okay, go,” he said.

We spent the night in the school. our MSR stove is not working we managed to arrange some coal to cook with it.

The next day, I managed only 3 km before I was completely drained.

We found a farm and asked if we could stay there. They kindly agreed.I tried to sleep the whole day while Sandra and David, our newfound friend, went to buy food from a town 5 km away.

The next morning, I woke up with a swollen, unrecognizable face. Panic set in.

We were in a country with one of the world’s weakest healthcare systems. My body was reacting in strange ways, and I had no energy to fight or even think rationally.

For a moment, we seriously considered finding a car to take us to Abidjan, where healthcare is better. We even thought about booking a flight back to Germany for proper treatment.

At that moment, David mentioned that he takes his children to a hospital 10 km away. He offered to bring us there on his motorcycle.

While waiting at the hospital, we met Dr. Chris and Bob, a board member from the U.S. who was visiting for a few days. Another test confirmed I still had malaria, along with inflammation caused by my weakened immune system .Dr. Chris immediately offered us a place to stay in her guesthouse and gave me a new treatment protocol.

We spent a few days there and got to know her. She is a true hero—someone who spent years working in different countries with an organization that helps people in crisis. After retirement, she returned to Liberia, to the town where she grew up, to improve the healthcare system.

She stayed in Liberia during the Ebola outbreak and survived with her entire team.

What started as a small tent hospital has now grown into a fully functioning facility that provides healthcare and education to hundreds of thousands of people.

We stayed for a week, during which we visited the community to learn more about the incredible work Dr. Chris does. We also had the opportunity to hear about her new project, Project 44. The project aims to provide education and opportunity to young people in Liberia. You can learn more about it on their website here: Project 44.

Project 44 will be dedicated to supporting the development of the next generation of leaders in Liberia. The organization focuses on providing access to quality education, vocational training, and personal development, helping young people build the skills they need for the future.

David was the one who brought us to the hospital and helped us with so many things, including buying groceries, finding drinking water, and assisting with various other needs.

Even though cycling through Liberia has been the most challenging experience so far, the Liberian people are among the most helpful and welcoming we’ve met. Despite the many frustrating encounters with the police and immigration, our exit from the country was smooth. I wanted to take a photo at the border crossing, and the police officer said, “Sure, I want to take a photo with you too!”

I feel a bit stronger now but the decision to continue or not we will be in Abidjan Ivory Coast.

Leave a Reply